Most Pagans, Heathens, Witches and those who study Scandinavian history are familiar with the Elder Futhark Runes and other variants of them that evolved during and after the Viking Age. However there are many other types of Runes that can be found throughout Europe and even stretching into Siberia. I have been studying Runes for many years and find some very interesting commonalities between all of these different types of Runes which at some point I will share. But for now I want to share with you all some very interesting Runes you may have never heard of which are the Polskie/slowiańskie runy (Polish Runes), Venedské Písmo (Vendic/Slavic Runes), Székely-Hungarian Rovás (Hungarian Runes) and the Finnish Script (suomalainen kirjaimisto).

Polskie/slowiańskie runy (Polish Runes)

Most people dealing with runes have probably heard of the Scandinavian futhark runes. These are probably the most popular runes, also used in magic and runic tarot. However, they do not illustrate the complete alphabet, there are many sounds missing, not to mention Polish ones, such as “Ą”, “Ę”, “CZ”, “SZ”, “DZ”, etc. Therefore, it is impossible to write with them. in the Polish language. It is true that I found pages about how to write a name in futhark, but it is very shallow and simplified, where one rune should be assigned many different sounds, such as the rune Kenaz is assigned the sound “K”, as well as “C”. Probably because the Kenaz rune looks like the Latin “C”, and this letter is missing in the futhark. However, this is incorrect thinking, as “C” is pronounced completely differently than “K”. “C” is dental and “K” is pharyngeal.

As Winicjusz Kossakowski proves in his study “Polish runes have spoken”, each rune has its origin. Namely, the rune illustrates which speech organs should be used to pronounce a given sound. And so, reading the letter by sound, the word was pronounced. This means that the runes were not a predetermined script. The most important thing was to draw the organs of speech so that another person could read them. Therefore, the set of runes could be different, the signs assigned to the same letter could be rotated, slanted or vertical, as well as completely different from each other, but as long as the main rule was adhered to, it did not cause major problems. SOURCE

Venedské Písmo (Vendic/Slavic Runes)

Before the arrival of Cyril and Methodius, in pre-Christian times, our ancestors, like many other European nations, used the runic script. The old Germans called this script vendic runic. Among the ancient Slavs, runic inscriptions were preserved primarily on idols and objects of religious significance. The most significant archaeological discovery in this area was made on the territory of today’s Germany (where an advanced Old Slavic culture once resided) in the area of the city of Retra. On the found statue of Perún, the prayer “Percun Devve i ne ruse i v neman” is engraved with ancient Slavic runes, which in translation means “By steam, God, heaven to no one”, on the statue of Belboga is engraved “Licjevajam tim Bilbocg” which means “I represent herewith Belboga”, the words “Radegast” and “Rjetra” are on the top of the statue of Radegast, “Podaga” is written on Podaga’s sacrificial plate, and “Cernebog” is written on Chernobog’s sacrificial bowl.

A very interesting hypothesis regarding Slavic runes was elaborated by Antonín Horák in his work “About the Slavs completely different”, where he expressed the assumption that the Old Slavic runic inscriptions carved into the rock on the Velestúr hill are thousands of years old, come from the period of oppression of the Slavic population by Asian nomads and are alleged evidence autochthony of the Slavs in Europe and a clue pointing to their “dove” agricultural way of life (the effort to portray the nobility as descendants of Asian killers and the proletariat as descendants of peaceful Slavs was probably appropriate at the time). The work is certainly interesting in many ways and worth reading, although many of the claims need further investigation. SOURCE

One thing that rarely gets mentioned is that these Runes can and are used for divination magick but the use of these are always over shadowed by the Futhark. If this is something you want to explore further I recommend the following resources.

What does Slavic runes mean and their decoding

Slavic runes: meaning and scope

Székely-Hungarian Rovás (Hungarian Runes)

The Old Hungarian script (in Hungarian rovásírás) is the earliest known writing system amongst the Uralic languages. As early as the 6th century, Chinese accounts noted the Hungarian custom of writing with incised marks on small wooden tablets. The script may be derived from Old Turkic writing.

There is some discussion regarding the direction of writing; it appears that Old Hungarian was written both from right to left and from left to right. In very early times, when the script was written on wooden sticks, the stick was turned as each line was written so that the text appeared in boustrophedon style. The boustrophedon style was not used for writing larger texts on walls or manuscripts, which tended to be written from right to left. Significant discussion has centered around this issue in the context of encoding the script for use on computers. Academic preference used to be generally for a left to right directionality, but modern users are more likely to write it from right to left, and that is now regarded as the default.

There are 45 basic letters in the script, which are able to represent all the sounds of Hungarian. That is not to say the orthography was phonemic; vowels were only written where it was ambiguous to omit them. Letters could be combined to form numerous ligatures. Historically, ligatures were not standardized, but used freely and inconsistently throughout handwritten texts. The same sequence of sounds could optionally be written with multiple signs or with a ligature. The script employed a single case, although the first letter of proper nouns was sometimes written slightly larger than the rest. There were also some non-alphabetic symbols, the functions of which seem to be unclear. SOURCE

Finnish Script (suomalainen kirjaimisto)

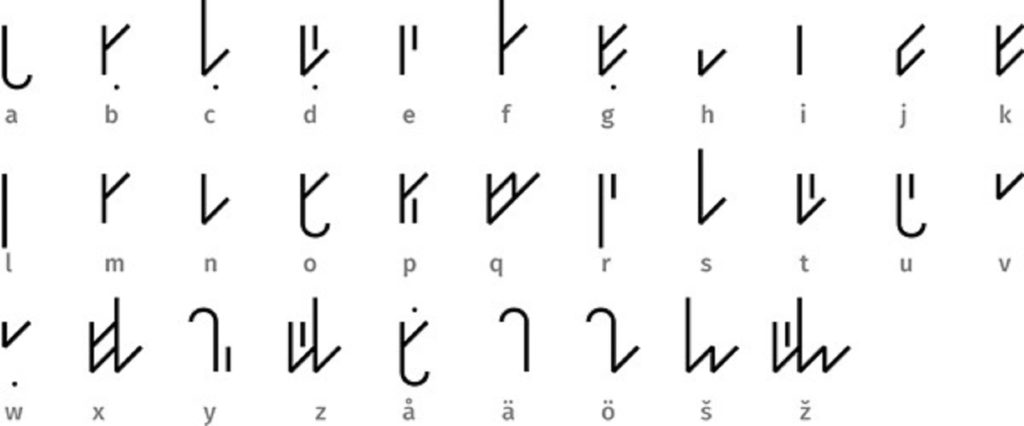

The Finnish script was invented by Sascha Mücke in an effort to create a writing system for Finnish that reflects the language’s phonological simplicity and clarity with its perfectly symmetric vowel harmony.

Notable features

- Type of writing system: alphabet

- Direction of writing: left to right

- There is a one-to-one correspondence between its letters and the Latin letters of the Finnish alphabet currently in use. The symbols have some featural characteristics of their corresponding sounds, most notably:

- High vowels (ä and ö, y) have a curve at the top while their corresponding low vowels (a, o, u) have a curve at the bottom; the neutral vowels e and i are not curved

- The weak consonants v, j and h are smaller than strong consonants, e.g. p or k

- Liquids (r and l) are longer at the bottom while (voiceless) fricatives (s, f) are longer at the top

- letters that typically only appear in loanwords (b, c, g, w and å) are considered variations of similar sounding letters and marked with a dot (analogously to b and g also d is marked as a variation of t, though it appears considerably more often than the former two)

- some other letters that typically only appear in loanwords (q, x, z, š and ž) are written as multiple letters (kv, ks, ts, sh and tsh)

Within a word the letters are placed directly adjacent to and connecting to each other, continuing lines should ideally be written with a single stroke (e.g. when writing no the diagonal lines of n and o should be written as one stroke). Words are separated by spaces, punctuation marks are the same as in the Latin script, optionally centered vertically (as in the example below). Also the script uses Arabic numbers. SOURCE

Further Resources:

Rovás, The Székely – Hungarian Alphabet

Unknown Polish/Lechite Alphabet?

Slavic Runes in the Research of Polish Scholars in the 19th Century