The history of the ancient Roman Empire has been a fascination of mine for decades and I have always enjoyed anything and all things from that amazing time period from its fruition to the fall of the Roman empire and into the time of the Byzantine Empire. The humble beginnings of Rome far before it became an empire has a really interesting story regarding two orphaned brothers and a She-Wolf simply known as La Lupa and the First lady of Rome. From this it has been always recognized that Rome was founded on April 21, 753 BCE. So today’s blog post will be covering all about Romulus, Remus and the famous She-Wolf of Rome.

La Lupa the She-Wolf

According to tradition, Rome was founded in 753 B.C. by the twins Romulus and Remus. Sons of the god Mars and a mortal woman named Rhea Silvia, a direct descendant of Aeneas, the twins were abandoned by their uncle in the Tibur river. A she-wolf discovered them on the banks of the river and suckled them until they were taken in by a passing sheperd, Faustulus. Faustulus raised the boys together with his own twelve children until they decided to found a city of their own. They chose the spot by the Tibur where they had been rescued by the wolf, which was near the base of the Palatine hill in Rome. The representation of the wolf suckling the twins became a popular subject in Roman Republican and Imperial art. SOURCE

Cristina Mazzoni, She-wolf: The Story of a Roman Icon. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010

“Lupus est homo homini.” Plautus Asinaria 495

This famous quotation, through its various translations, perfectly encapsulates the themes explored in Cristina Mazzoni’s new book. Man is a wolf to other men—as Plautus undoubtedly meant it——but a wolf can also be interpreted as a human being in particular circumstances. In both Italian and Latin the word lupa can describe a she-wolf or a prostitute, either a ferocious animal or a female human of voracious sexual appetites. This paradox has informed interpretations of the legend of Romulus and Remus since antiquity, where the she-wolf figures as animal, mother, and whore simultaneously, and the complexity and ambiguity of this formative being have given her long life as a symbol representing a myriad of concepts, individuals, and entities. Mazzoni sets herself the ambitious task of exploring the she-wolf in all her forms and interpretations, from the famous Lupa Capitolina to her appearance in modern art, archaeology, poetry, and literature. Continue reading HERE.

Symbolism of the She-Wolf

The she-wolf of Rome represents the following concepts:

- The she-wolf represents Roman power, which made her a popular image throughout the Roman Republic and Empire. The connection between the Roman state and the she-wolf was such that there were at least two dedications to the she-wolf performed by priests.

- Wolves, especially she-wolves, are a sacred animal of the Roman god Mars. It is believed that they acted as divine messengers, thus seeing a wolf was a good omen.

- The she-wolf is associated with the Roman Empire’s wolf festival Lupercalia, which is a fertility festival that starts at the estimated spot where the she-wolf nursed the twin boys.

- The she-wolf also comes across as a mother-figure, representing nourishment, protection and fertility. By extension, she becomes a mother-figure to the city of Rome, as she lies at the very heart of its establishment. SOURCE

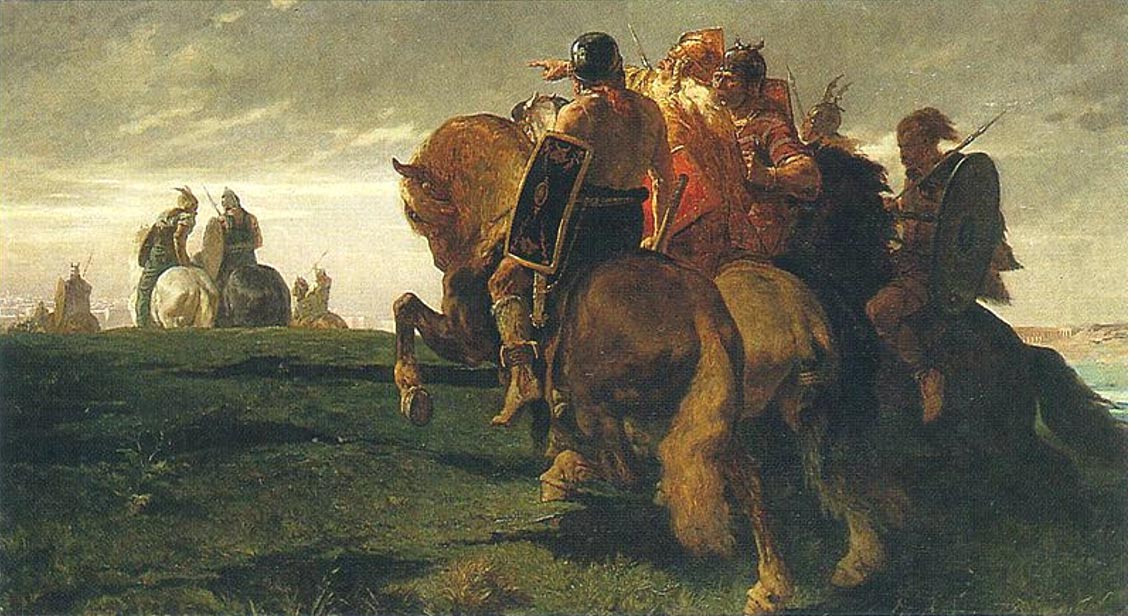

Romulus and Remus

Romulus and Remus were the direct descendants of Aeneas, whose fate-driven adventures to discover Italy are described by Virgil in The Aeneid. Romulus and Remus were related to Aeneas through their mother’s father, Numitor. Numitor was a king of Alba Longa, an ancient city of Latium in central Italy, and father to Rhea Silvia. Before Romulus’ and Remus’ conception, Numitor’s reign was usurped by Numitor’s younger brother, Amulius. Amulius inherited control over Alba Longa’s treasury with which he was able to dethrone Numitor and become king. Amulius, wishing to avoid any conflict of power, killed Numitor’s male heirs and forced Rhea Silvia to become a Vestal Virgin. Vestal Virgins were priestesses of Vesta, patron goddess of the hearth; they were charged with keeping a sacred fire that was never to be extinguished and to take vows of chastity.

There is much debate and variation as to whom was the father of Romulus and Remus. Some myths claim that Mars appeared and lay with Rhea Silvia; other myths attest that the demi-god hero Hercules was her partner. However, the author Livy claims that Rhea Silvia was in fact raped by an unknown man, but blamed her pregnancy on divine conception. In either case, Rhea Silvia was discovered to be pregnant and gave birth to her sons. It was custom that any Vestal Virgin betraying her vows of celibacy was condemned to death; the most common death sentence was to be buried alive. However, King Amulius, fearing the wrath of the paternal god (Mars or Hercules) did not wish to directly stain his hands with the mother’s and children’s blood. So, King Amulius imprisoned Rhea Silvia and ordered the twins’ death by means of live burial, exposure, or being thrown into the Tiber River. He reasoned that if the twins were to die not by the sword but by the elements, he and his city would be saved from punishment by the gods. He ordered a servant to carry out the death sentence, but in every scenario of this myth, the servant takes pity on the twins and spares their lives. The servant, then, places the twins into a basket onto the River Tiber, and the river carries the boys to safety. Continue reading HERE.

Establishing a new city had its price, and Romulus was forced to defend the nascent community. As he tirelessly safeguarded Rome, Romulus proved that he was a competent leader and talented general. Yet, he also harbored a dark side, which reared its head in many ways and tainted his legacy, but despite all of his misdeeds, redemption and subsequent triumphs were usually within his grasp. Indeed, he is an example of how greatness is sometimes born of disgrace.

Regardless of his foreboding flaws, Rome allegedly existed because of him and became massively successful. As the centuries passed, the Romans never forgot their celebrated founder.

Further Resources

The legend of Romulus and Remus