Caratacus (Brythonic *Caratācos, Middle Welsh Caratawc; Welsh Caradog; Greek Καράτακος; variants Latin Caractacus, Greek Καρτάκης) was a first-century British chieftain of the Catuvellauni tribe, who led the British resistance to the Roman conquest.

Before the Roman invasion Caratacus is associated with the expansion of his tribe’s territory. His apparent success led to Roman invasion, nominally in support of his defeated enemies. He resisted the Romans for almost a decade, mixing guerrilla warfare with set-piece battles, but was unsuccessful in the latter. After his final defeat he fled to the territory of Queen Cartimandua, who captured him and handed him over to the Romans. He was sentenced to death as a military prisoner, but made a speech before his execution that persuaded the Emperor Claudius to spare him.

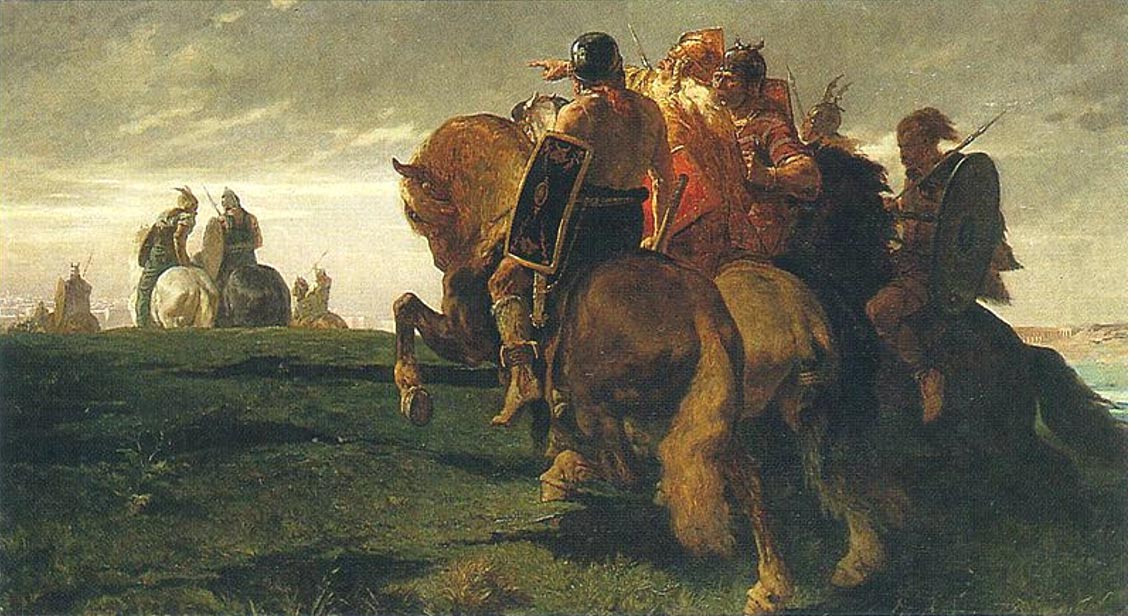

The legendary Welsh character Caradog ap Bran and the legendary British king Arvirargus may be based upon Caratacus. Caratacus’s speech to Claudius has been a common subject in art.

Caratacus is named by Dio Cassius as a son of the Catuvellaunian king Cunobelinus. Based on coin distribution Caratacus appears to have been the protégé of his uncle Epaticcus, who expanded Catuvellaunian power westwards into the territory of the Atrebates. After Epaticcus died about 35 A.D., the Atrebates, under Verica, regained some of their territory, but it appears Caratacus completed the conquest, as Dio tells us Verica was ousted, fled to Rome and appealed to the emperor Claudius for help. This was the excuse used by Claudius to launch his invasion of Britain in the summer of 43 AD. The invasion targeted Caratacus’ stronghold of Camulodunon (modern Colchester), previously the seat of his father Cunobelinus.

Cunobelinus had died some time before the invasion. Caratacus and his brother Togodumnus led the initial defence of the country against Aulus Plautius’s four legions, thought to have been around 40,000 men, primarily using guerrilla tactics. They lost much of the south-east after being defeated in two crucial battles, the Battle of the River Medway and River Thames. Togodumnus was killed (although John Hind argues that Dio was mistaken in reporting Togodumnus’ death, that he was defeated but survived, and was later appointed by the Romans as a friendly king over a number of territories, becoming the loyal king referred to by Tacitus as Cogidubnus or Togidubnus) and the Catuvellauni’s territories were conquered. Their stronghold of Camulodunon was converted into the first Roman colonia in Britain, Colonia Victricensis.

Resistance to Rome

We next hear of Caratacus in Tacitus’s Annals, leading the Silures and Ordovices of Wales against Plautius’ successor as governor, Publius Ostorius Scapula. Finally, in 51, Scapula managed to defeat Caratacus in a set-piece battle somewhere in Ordovician territory (see the Battle of Caer Caradoc), capturing Caratacus’ wife and daughter and receiving the surrender of his brothers. Caratacus himself escaped, and fled north to the lands of the Brigantes (modern Yorkshire) where the Brigantian queen, Cartimandua, handed him over to the Romans in chains. This was one of the factors that led to two Brigantian revolts against Cartimandua and her Roman allies, once later in the 50s and once in 69, led by Venutius, who had once been Cartimandua’s husband. With the capture of Caratacus, much of southern Britain from the Humber to the Severn was pacified and garrisoned throughout the 50s.

Legends place Caratacus’ last stand at either Caer Caradoc near Church Stretton or British Camp in the Malvern Hills, but the description of Tacitus makes either unlikely:

[Caratacus] resorted to the ultimate hazard, adopting a place for battle so that entry, exit, everything would be unfavorable to us and for the better to his own men, with steep mountains all around, and, wherever a gentle access was possible, he strewed rocks in front in the manner of a rampart. And in front too there flowed a stream with an unsure ford, and companies of armed men had taken up position along the defenses.

Although the Severn is visible from British Camp, it is nowhere near it, so this battle must have taken place elsewhere. A number of locations have been suggested, including a site near Brampton Bryan. Bari Jones, in Archaeology Today in 1998, identified Blodwel Rocks at Llanymynech in Powys as representing a close fit with Tacitus’ account. SOURCE